While analyzing the origins and methods of processing data may seem tedious, I have found that such a discussion carries great importance when considering the humanist’s relationship with the text. In particular, we should always be cognizant of where our data comes from, if it has been processed, and if so, who processed it. Without such considerations, we may confine ourselves to subpar versions of texts when superior ones are accessible, or, conversely, we may spend excessive amounts of money and resources on acquiring high-quality reproductions when free public domain resources suffice for our purposes.

A Warning

Rather than just speaking in generality, though, I will give an example. I am currently in a book club, and we are reading (as strange as it may sound) Laurence Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. A member of the group purchased a copy of the text (which I will not refer you to for reasons that will become apparent momentarily) which seemed strange in comparison to every other person’s version. In particular, the formatting was awkward (e.g. all the page numbers were in Roman numerals), the chapter designations differed from ours (the owner of the text ended up reading twice as much as everyone else because of this), there were no explanatory notes (which are not required, I guess, but are incredibly useful in such an old and confusing novel), and the text did not even have a copyright page or any of the usual prefatory material found in a book (making it seem like something you would find on the black market (who would buy a copy of Tristram Shandy on the black market, however, remains an open question)). We eventually discovered that this person’s version of the text was a mere replication of the public domain Project Gutenberg reproduction, and I am convinced that whoever “published” the text simply copy and pasted from this website. All of us in the book group were rather shocked at the shadiness of “publishing” a text in such a state, and I take it as a lesson to always check for the quality of a text before purchasing it.

I bring up this story to demonstrate that the transition from raw to processed data is not always a positive process, but can diminish one’s ability to understand the material. Thus, when analyzing data, we should always ascertain that our methods of processing always either improve the text or allow for unique interpretations of the text and that we never simply release an inferior version of something already widely available.

The Procession of Data with Particular Reference to Tristram Shandy

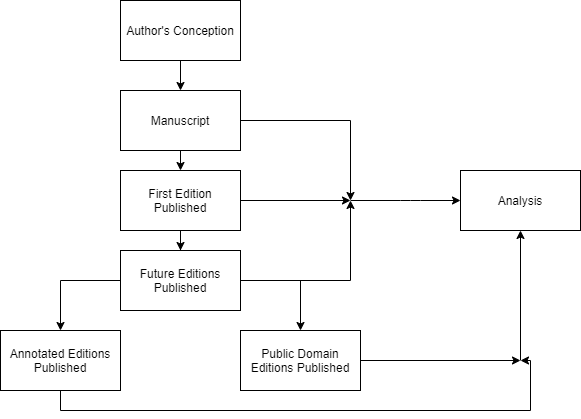

I would now like to analyze how this piece of humanities data (i.e. the text of the novel) has been processed. When thinking about how Sterne’s novel has transformed from raw to processed data, I developed the following diagram (which I will admit right now is rather basic, but I think it will help elucidate my thoughts):

At the top of the diagram is data in its rawest possible form: entirely contained within the mind of the author (in this case, Sterne). From there, the author writes these thoughts down, creating a manuscript. This is the rawest data accessible to others (at least if it is made publicly available), and it is processed to the extent of the author’s cognitive filter, which seems to be rather minimal in the case of Sterne. Next, the author publishes the manuscript into a first edition, which is generally the first text available to read. Given the large editing and revision process generally necessary to turn a manuscript into a published book, the data is considerably more processed, but still reminiscent of the urtext. If the work is successful, as Tristram Shandy was, further editions are published which potentially fix any typographical mistakes, include author prefaces or illustrations, and reflect on the work’s success. While these versions are more processed than first editions, they do not differ too drastically. Next, after the text has entered the public domain and established itself as an important historical work, critical editions are published which contain explanatory notes and selections of seminal essays, like the Norton Critical Edition or the Oxford World’s Classics Edition, and online public domain versions are made available through resources like Google Books and Project Gutenberg (although, if my narrative above carries any weight, these versions should only be referenced lightly). The former of these generally are the most processed versions of the text accessible, because of the wealth of information added to the original data, while the latter are frequently reproductions of the early editions of the text, and hence are arguably less processed than earlier efforts. Finally, throughout all these processes of processing, theorists and critics busily analyze the text, using various theoretical frameworks to look for meaning, or using various meanings to justify theoretical frameworks. Analysts may compare how the text has changed throughout the years, or they may be ambivalent as to which version to which they refer. Only at this stage does the data transform into its most processed form, as not only has the text been elaborated upon, but, moreover, only the elements necessary for analysis are included. In effect, the analyst takes a text, determines which parts are most important, and casts asides the rest (not necessarily because the rest is unimportant, but because only a limited amount of the text can be discussed in a reasonable amount of time (if we had all the time in the world, then this would likely not be an issue (but that is going down a rabbit hole way beyond the scope of this blogpost))).

I think this diagram indicates that processing data is the only way to get meaning out of a text, and that while too much processing may hinder one’s ability to successfully interpret a text, everything we do when looking at a work is a system of processing data. One thing this diagram omits, however, is how data becomes processed as it enters into the reader’s mind: transforming from words on a page or screen to a cognitive understanding within the interpreter. In effect, there is no way to observe data without processing it to some extent, as this is the only way to extract meaning.

A Discussion of Digital Data

As a means of investigating the relevance of digital tools to studying literary texts, I put the first two volumes of Tristram Shandy into a text analyzer to see how the results compared with my own experiences (I have to admit that one of the benefits of online public domain versions is how they expedite the process of copy and pasting large amounts of text (I would not have done this part of the assignment if I had to rewrite the entire text)). Overall, I found some not-so-surprising results as well as one result worthy of more investigation. The unsurprising results include the prevalence of masculine pronouns (likely typical of an eighteenth-century novel), the personal pronoun “I” (likely typical of a first-person novel), and the second-person pronoun “you” (again, likely typical of a metafictional novel (I would need more data about novels from similar genres and time-periods for a more accurate analysis, though)). The unexpected result is the prevalence of references to the side-character Uncle Toby, indicating that he may be more important than the work initially lets on, but this would require some more careful close reading in order to find a suitable explanation.

These results demonstrate that digital tools can improve one’s interpretative abilities of shorter works like novels and poems, as long as they are utilized in conjunction with traditional close-reading techniques. Any project which relies on an analysis of a large body of works (something like all the works of Shakespeare), or involves interpretations beyond close reading (like geographical mapping), would likely require a stronger reliance on digital tools, as doing everything manually would be unreasonable. However, for an analysis of a single passage, a digital tool like the one utilized here seems somewhat unnecessary and might not provide any meaningful results. As I am yet unfamiliar with most tools, I am sure ones better suited for smaller selections of data exist, but as it stands, I only see value in the use of digital tools to analyze humanities data in conjunction with traditional methods and as a means of making manual processes more efficient. I am excited, however, to see different ways in which digital tools can interact and interpret literary texts.