Now that we are starting to use data collecting methods in our analyses of literary texts, I have realized how detail-oriented and deliberate the process needs to be in order to discover any meaningful results. While one could take a large amount of text, plug it into some digital tool, and analyze the results, the data would be much too general to make any specific and meaningful claims (although that more general information could have its uses if someone wants to make generalizations or large-scale comparisons). However, to faithfully analyze a text using digital tools to supplement, but not to replace, manual close-reading techniques, one needs to be specific in choosing which data to examine, in order to avoid collecting a surfeit of complex information. Additionally, throughout the process of this lab, I have discovered the value of digital tools in making manual processes more efficient and in diagramming the data developed through reading. In effect, both “traditional” and digital methods have benefits and weaknesses, but they work well in conjunction with each other. But enough generalization; here are some of my results:

Traditional Data-Collecting Methods

In analyzing Danielewski’s “Clip 4,” I considered the ways in which characters directly refer to other individuals, in order to examine any distinguishing characteristics that may give insight into personality types. I also performed this in order to find if there existed any distinguishing factors between how people provide references in academic prose versus in standard conversation, and I considered how this may reflect on academic institutions more generally. In particular, for my traditional data-collecting method, I compiled all the direct references by name to other persons, fictional or real, that I could find in the text, as well as which character made the reference, and a brief description for why that reference may have been made (although, this method used a spreadsheet to organize the information, so it was still rather “digital”). The data is given in the file below:

Reflecting on this data, I made some useful discoveries about the text, such as how the character Toland Ouse (either in a direct quote or as paraphrased by Realic S. Tarnen) makes thirty-eight references to others (not including all of Audra’s pseudonyms), while, in comparison, Tarnen makes twenty-nine. I consider this to be unexpected, because academic prose has a reputation for frequently making references to other texts and their relationships to the objects of study, while normal conversations usually do not feel as referential. This could indicate a misconception of mine in the levels of intertextuality in our communications, or it could indicate an element of Ouse’s character. Specifically, by making so many references to figures of popular and academic culture (some famous, some obscure, some real, some fake) he attempts to situate himself in his surrounding culture, potentially generating a sense of ethos and trust. By indicating his familiarity with significant cultural figures, Ouse cements himself as a member of society who can relate to others on a general level. However, this comes into conflict with Tarnen’s admittance that their “shallow knowledge of music” forced them to “double-check [Ouse’s] references later” (179),1 while Ouse was not familiar with “Darc’s The Zoo: Costruire Paradisi Di Buio” (180). This conflict indicates the difference in social group that Ouse and Tarnen occupy, in that they are unable to fully comprehend each other’s references to what they each perceive as important works.

In academic prose, writers make references to other works in order to situate their own work in a context of research, so that it will be seen as valid and important. This can be seen in the Caroline Weld’s research suggestions in the comment: “Might want to have a looksie at Yi-Fu Tuan’s Topophilia, Randy Malamud’s Reading Zoos and Cary Wolfe’s Animal Rites. Matthew Calarco’s Zoographies too. Top of my head. We can revisit” (171). This comment could be seen as Weld attempting to further ground Tarnen’s research in already established texts. However, those references are meaningless if the reader does not have any knowledge of them, and, for all intents and purposes, they may as well be fictitious. Thus, “Clip 4” demonstrates the fundamental rift that can exist between different cultural communities when they are unable to understand the significant figures and works in each other’s world. A sense of tension develops between Ouse and Tarnen, as well as between the reader and the text, as each attempts to grapple with the prerequisite knowledge required in order to effectively communicate with the other.

One action that could have further developed this method of data-collecting would have been to search each name referenced and determine the likelihood of it referring to a real person. Determining which character is more grounded in our reality, and which is more based in the fictional world of the story, would have provided great insight into how each character operates in relation to the rest of the text. Unfortunately, this would have been a rather time-intensive project, which I will leave for future considerations.

Digital Data-Collecting Methods

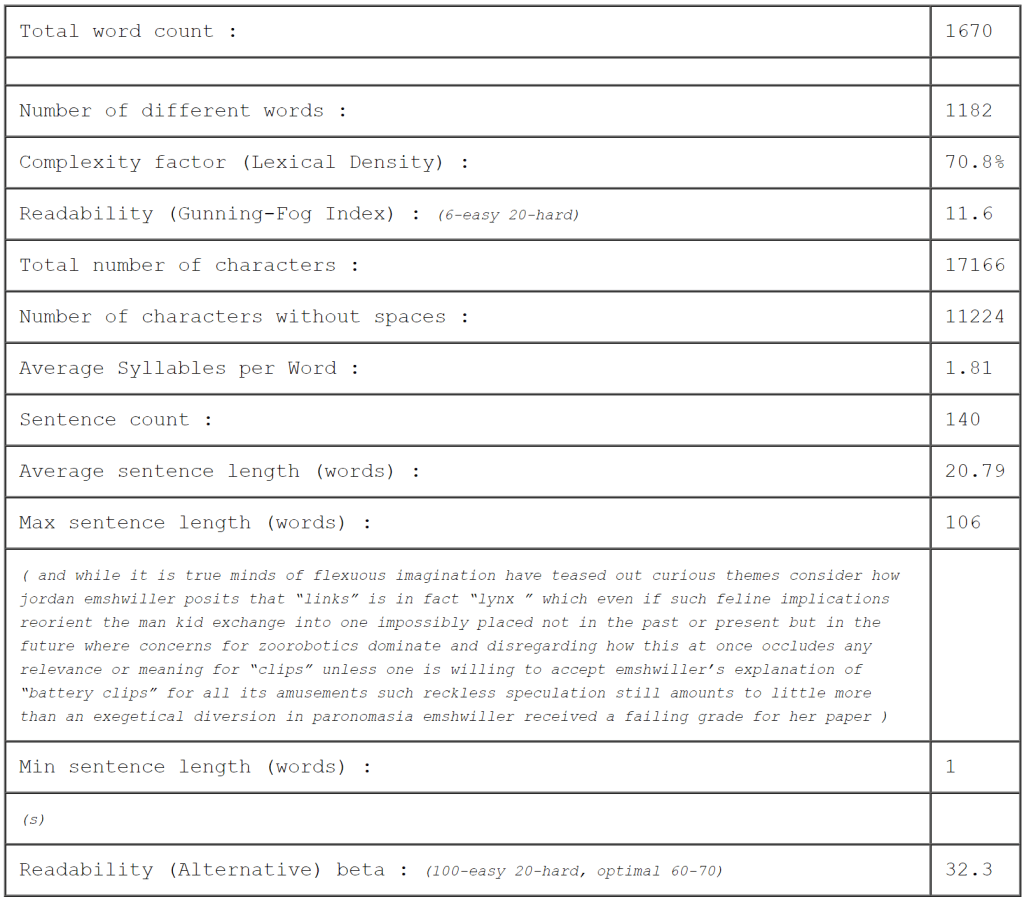

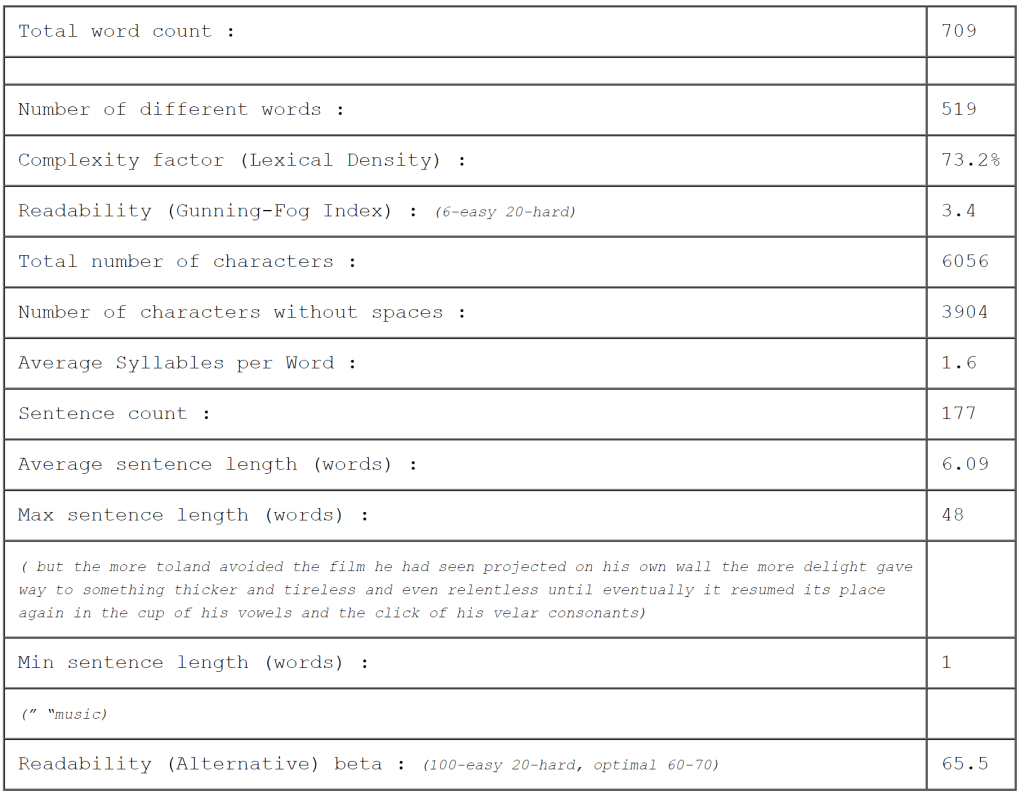

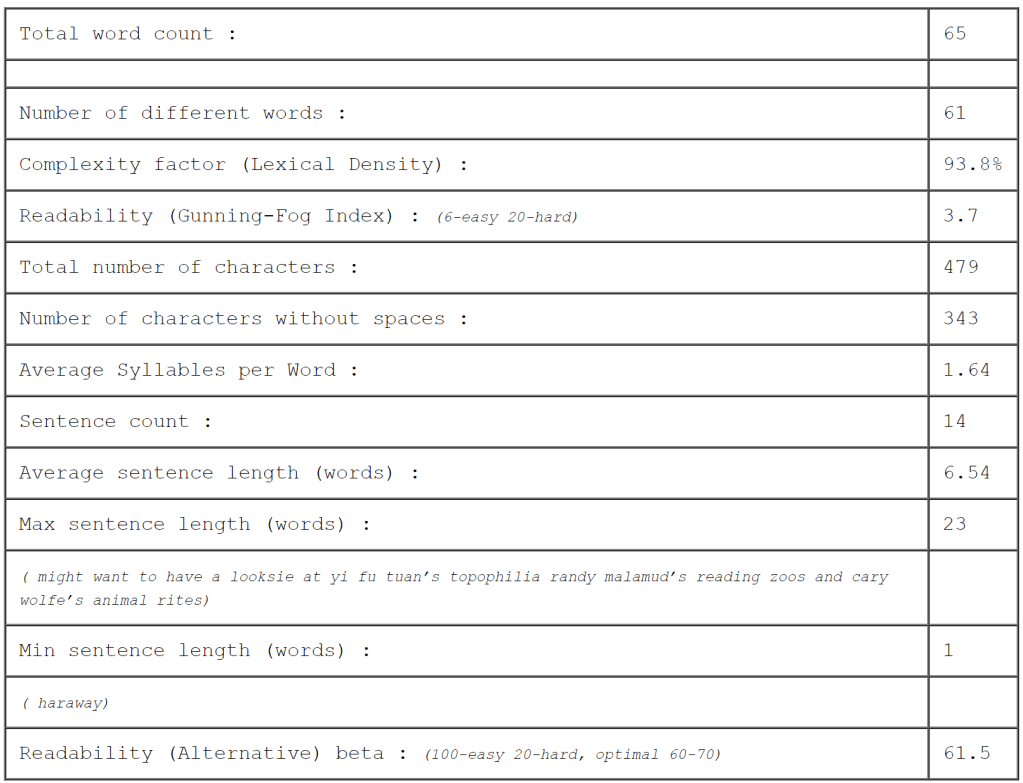

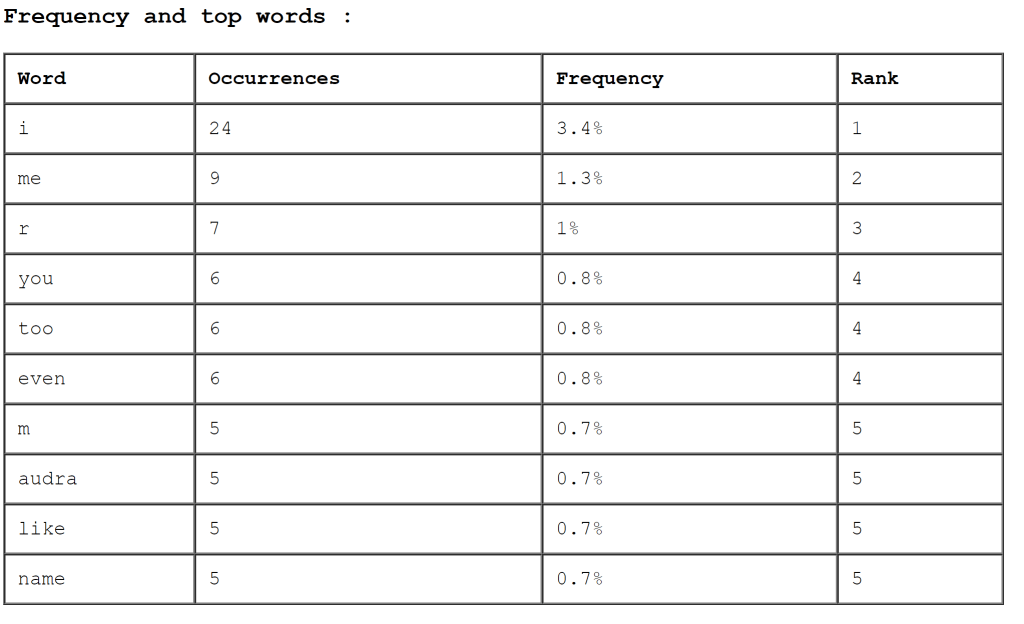

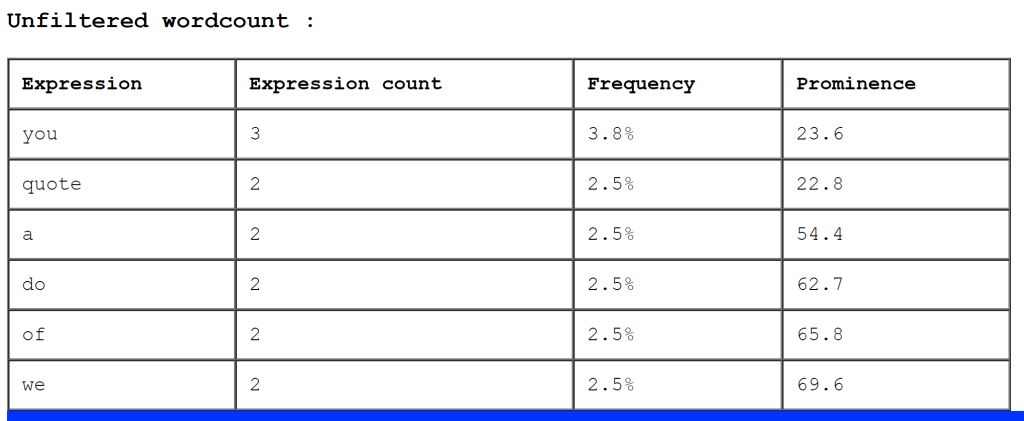

For the digital part of the lab, I utilized Textalyser in order to analyze the same topic as above and to find other significant differences in the ways we reference others in our communications. Specifically, I analyzed all the paragraphs of Tarnen’s academic prose in which they referenced another person or text, and compared the results to all the paragraphs in which Tarnen directly quoted or paraphrased one of Ouse’s references to another person. I also compared these results to all of Weld’s comments that contain a reference to another person (although this data in particular was relatively sparse, so the results should take this into consideration). I recorded data in this manner in order to ascertain if there was a specific distinction between how characters communicated and what kinds of words they utilized when referring to others, and I was curious if this would reflect at all on how the manners in which we communicate differ between an academic setting and a more personal environment.

First, here are Textalyser’s general results for the three pieces of data:

The first value I noticed was the distinction between the Gunning-Fog Index between the three texts: Ouse and Weld have similar results while Tarnen appears to write substantially more difficult prose. This result is fairly straightforward, however, as any form of intentional writing is likely to be more difficult to parse than a conversation or a handwritten comment. This also relates to the drastic distinction in the average number of words per sentence, because it is easier to craft long, intricate, and complex sentences in a written format as opposed to on-the-spot speech.

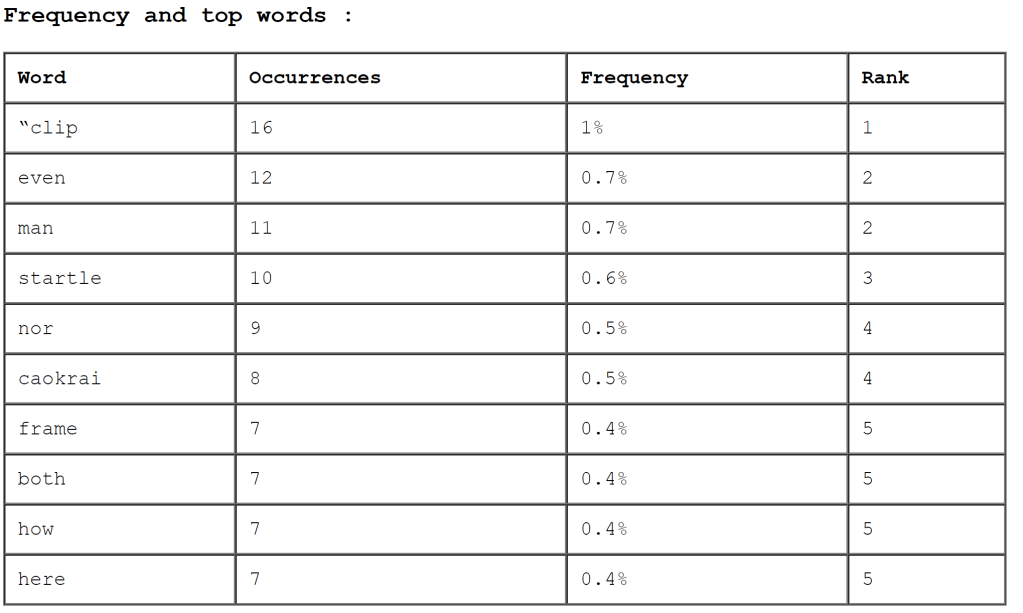

One possibly unexpected result is the fact that Tarnen has the lowest value for lexical density (70.8%), while Ouse’s score is slightly higher (73.2%), and Weld’s is drastically greater (93.8%). While Weld’s score could be attributed to the smaller sample of text, and the fact that most of the text analyzed consisted of names of people and titles of works, the relationship between Ouse and Tarnen’s scores is unusual. This could indicate that academic prose is more formulaic than informal speech, and that there is an expected pattern for how we should refer to other works, while conversational speech has a more impromptu feeling (I personally remember learning to cite sources in middle school by using templates). This data could also indicate a more fundamental difference in how Tarnen and Ouse communicate; however, this result can be elucidated much more clearly through the word-frequency tables given here:

There is a great deal of information packed into these three tables, and I could not possibly uncover it all, but here are some of my initial observations. First, Tarnen’s prevalence of references to Startle and Caokrai (two scholars) indicates how much of the research on “Clip 4” (the film inside the text) is based on the works of these two individuals. Tarnen could be seen as attempting to situate their work in the research of these two significant academicians, as much of the first half of the text discusses their arguments. Tarnen admits that the film “Clip 4” has not “in any way yielded an academic industry” (170), and this possibly provides justification for why they have to rely primarily on works of Startle and Caokrai.

Second, Ouse frequently utilizes first-person pronouns (“I” and “me”), indicating that his references are made as a reflection on their relationship to himself. Specifically, Ouse could be seen as using his familiarity with others in order to bolster his own reputation and how he relates to these significant individuals, enforcing the previous argument about him desiring to develop a sense of ethos and trust with Tarnen. This fixation on himself can be seen in the text when he describes the video of his daughter Audra drowning. His main takeaway at the end is that “She drowned that night. Alone. Calling out for me. Her lost— last call. Unheard. And yet somehow still witnessed” (184, emphasis added), so that even when reflecting upon her death, he still considers its relation to himself. Even in this traumatic scene, he inserts himself and the relevance the story has to his own existence.

Finally, while the data is limited, Weld’s use of the second-person pronoun “you” indicates that they are primarily focused on Tarnen and the state of the essay. All the references made by Weld are in the service of Tarnen, implying a potential hierarchy between the two characters where the former wishes to please the latter.

More still can be gleaned from this data, such as why Tarnen frequently uses the word “man,” or how Ouse uses the word “too” fairly often. However, exploring these possibilities would likely create even more questions with unclear answers, so I will again leave that for later consideration.

Visualizing Data-Collecting Methods

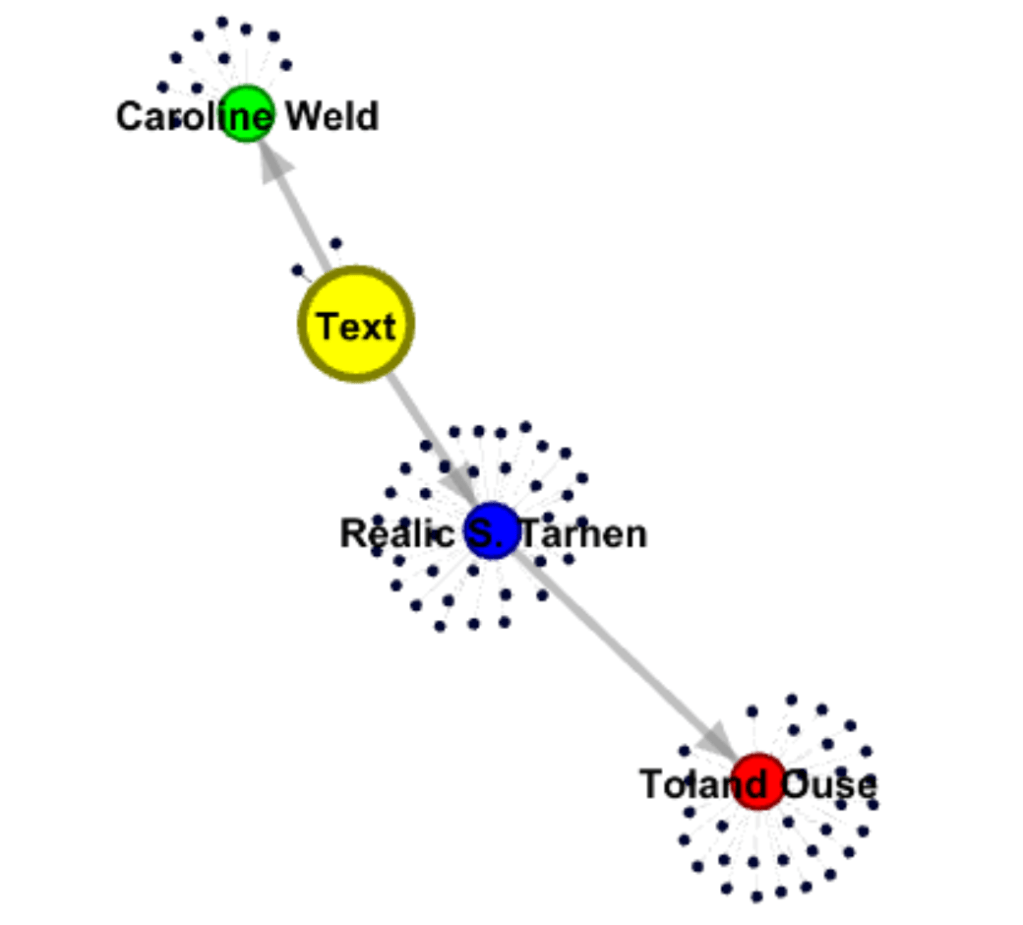

As a part of this lab, I also utilized the application Gephi in order to graphically visualize the manually-collected data above. I was, fortunately, able to import the spreadsheet into the program, making the data entry process much shorter, and I think the end-diagram nicely captures the information. Here is an image of the final result:

While no new information is included in the above image that cannot be found in the spreadsheet (and in some sense, the spreadsheet contains more information), the image works well as an accompanying element to clarify the many rows of text in the excel file. Moreover, I think this idea applies in general: visual aids work well to explain and succinctly summarize one’s data, but they should rarely be used as the only means of expressing such information, because some important details will be lost in the process. It would be difficult to develop a diagram that contained all the data collected while still looking pleasant.

Comparing Data-Collecting Methods

Now that all the data-collecting and organizing processes have been completed, it is time to consider each methodological approach’s strengths and weaknesses, because no one method is inherently better than another. The first thing I should mention, however, is that manually collecting data is a rather tedious process. Having to gloss over the entire text looking for named individuals took a decent amount of time to complete, and I do not feel entirely confident that I found every single person mentioned. Humans are generally error-prone when it comes to finding minute details, so all analysis derived from manually-collected data needs to take the potential for mistakes into consideration. Conversely, computers do not make mistakes (except in the rare chance where a cosmic ray changes a byte of data in its memory banks). Any mistake from computer-collected data will likely be due to an issue in the computer’s programming, or an issue in the user’s request.

However, while computer-collected data may be more “reliable,” it is often more general and harder to apply to a specific analysis. Specifically, in this lab, I was able to collect data for a particular question I had about the text, and I was able to choose for myself what was important and what was unnecessary. Even though there may exist some ambiguity as to what should be considered important, I had the personal freedom to make that decision for myself. However, the text-analyzing software utilized in this lab did not provide me with as much freedom to determine what data was significant and should be recorded (there are some options in the program, but they are still rather general). Thus, I was forced to apply more general data to a specific question, and I felt this provided with slightly less analytic opportunities. Thus, to summarize, manually-collected data, while more difficult to collect, has greater variability and can be more easily targeted for a particular question. Conversely, computer-collected data is much easier to collect, but due to this ease, it will generally be less specific and less personally detailed.

However, the above juxtaposition may only work in the context of this lab, as I am still new to considering literature from an analytic, numerical perspective. This is also one of the difficulties of this methodological approach to literary studies: there are some things that are difficult to quantify. While I looked at the number of references utilized by different characters, and examined word counts of different sections of the text, I could not objectively quantify the weight of each reference made, and not each use of a word carries the same weight. Some references seemed more important than others (such as Tarnen’s discussion of Startle and Caokrai), but others could easily disagree with my analysis and provide evidence against it. Unlike a mathematical theorem, there is no way to definitively prove most analyses of a text, and any collected data may be subject to scrutiny and dissent. In effect, any literary study will miss that sense of pure objectivity typically associated with scientific research, and any analysis should take this into consideration. However, this is not an inherently negative concept. What literary studies lose in objectivity, they more than make up for in the opportunity they provide for subjective thinking. While the scientific researcher must always fear not being objective enough, the literary scholar is allowed to consider data subjectively and analyze how personal biases and experiences have value in making conclusions. As I mentioned above, the manually-collected data can be targeted to answer a particular question of my own, and even the digitally-collected data was derived from my own judgments and discretion. I could choose which parts of the text I considered to be important without fear of being “objectively incorrect.” Thus, while this data may lose its value as a purely scientific artifact, it gains value as a human-developed object that one can utilize as a tool for exploring a personal relationship to a text.

Finally, as mentioned above, the process of data visualization helped to clarify and to explain the data, even if it did not technically provide any new information. While I would not go so far as to say that this visualization process was a necessary part of my data analysis, it allowed me to reflect more on what I considered as important, and it gave me the opportunity to numerically weigh that importance against the rest of the data. Overall, I viewed data visualization in the context of this lab as a nice way to quickly explain my analysis in an easy-to-understand diagram, but any detailed analysis will generally require more than just a pretty picture (unless the diagram itself is the focal point of one’s research).

Note:

- All references are to Mark Z. Danielewski’s “Clip 4” which can be found here.