Jordan Abel’s process in writing “Injun” inspires one to consider and question one’s relationship to the political and ideological undercurrents of historical texts and how they relate to present-day inequalities and injustices. By data-mining novels from and about the “Old West” for instances of such a derogatory term, and then using these texts to craft his own poetry, Abel uses the voices which have historically silenced indigenous peoples in order to develop his own voice and put forward his own perspective on the genocides which occurred on the land we refer to as “North America.” More generally, following Abel’s methodology allows one to examine how any text, regardless of content or region of origin, can be utilized to develop one’s own artistic voice through a personal relationship to the text. Whether one utilizes this methodology for political purposes, for comedic effect, or for some other form of artistic expression, a new and valuable perspective will be realized, even if all the words come from somewhere else. In my case, going into this lab, I wanted to explore facets of my identity as they relate some novel which had a significant impact on my life, and I think I created something worthwhile.

My Process:

For a source text, I chose James Joyce’s Ulysses, and I searched for all instances of the word “Jew.” To explain my word choice, it would be helpful to know that I was raised Jewish (going through many of the traditional ceremonies), but I do not currently practice the religion. I still identify as Jewish, to some extent, but I do not consider Judaism to be in the forefront of how I construct my personal identity. (It is difficult to explain, to be honest, because I myself do not fully understand how Judaism factors into my conscious perception of myself. It plays some role, but it is not central.)

I chose Joyce’s (in)famous novel, because of the strange sense of camaraderie I felt with the protagonist, Leopold Bloom, who also is “technically” Jewish, even if he does not fully identify as such. There are other reasons why I thoroughly enjoyed this novel (despite the fact that I understood only a small percentage of it while reading), which I will not discuss here (as that would necessitate a blog of its own), but I frequently think about its depiction of the effects of an inherently anti-Semitic culture on a Jew’s construction of self-consciousness. Thus, I wanted to use Joyce’s text as a means of developing and considering my own Jewish identity and my relationship with the history of the culture.

After deciding the text and word came the process of actually data-mining the Project Gutenberg edition, which, as you could imagine, was rather tedious. There were eighty-one instances of the letter combination “j” – “e” – “w” (most of these occurrences were the actual word “Jew,” but a few were as part of the word “jewel”), and compiling all these instances took a decent amount of time. One of the unusual circumstances I encountered was the fact that the last chapter of Ulysses contains multi-page spanning sentences, some of which would contained an instance of my chosen word, so I had to copy long strings of text into my source document. In order to incorporate these “sentences” into my poem, I decided to make their font size as small as possible while still being “legible.” Next, I printed out the source document, which can be found here:

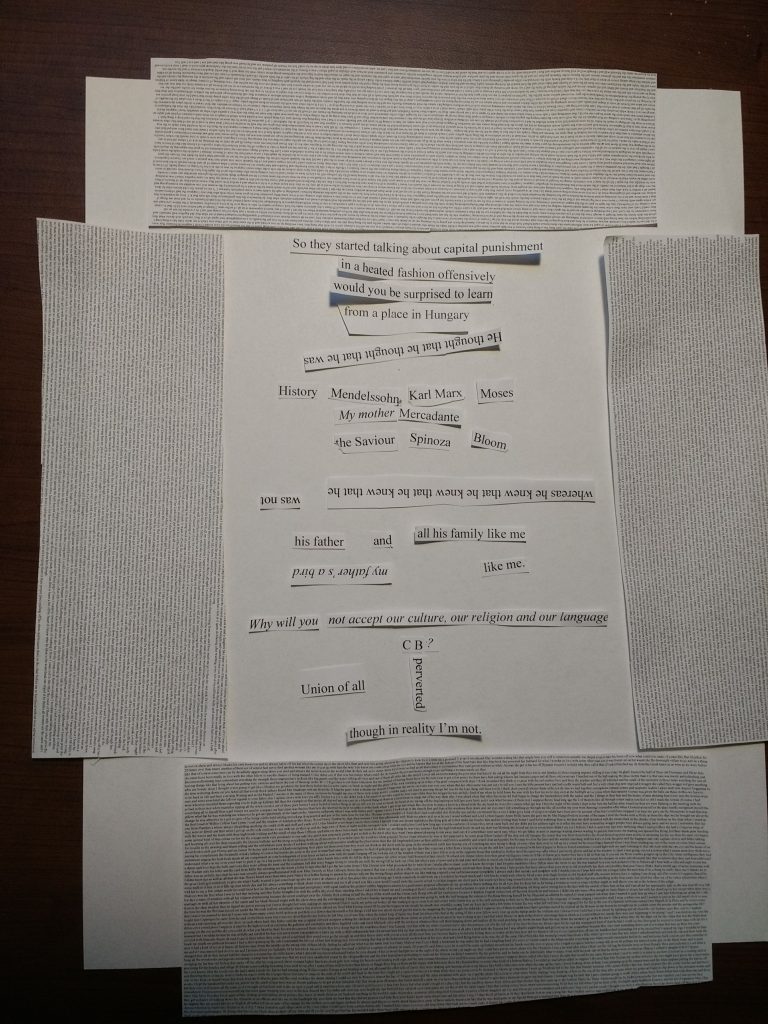

Then, I took all the sentences which struck me as particularly meaningful, cut them up, and arranged them on a blank sheet of paper. Feeling satisfied with my end result, I finally recreated the poem digitally in a word processor. Below is a photograph of the physical poem and a PDF of its digital recreation:

I will not discuss the actual content of the poem, as I want to leave it open to interpretation.

Comparing Methodologies:

While my process in developing this poem was inspired by Abel’s data-mining methodology, there were several key differences. Namely, I only examined one text while he examined many, meaning his work ultimately contains more material (although, my poem technically has more words (nearly 16,000), but most of them are effectively unreadable). However, a more substantial difference is that when crafting the poem itself, I was not as concerned with the ways in which my source text appropriated the word in question, as I focused more on my personal reflection. That is not to say Abel’s poem is not personal (as it most assuredly is). Rather, I mean to say that my poem did not fully (or at least explicitly) take into consideration how Jewish people were represented in early-twentieth-century literature, and how our modern-day conceptions of Judaism were developed by these representations.

In effect, I would say that my poem was politically inspired, but not fully politically motivated. However, I would also argue that any piece of writing is politically inspired, because it will necessitate ideological assumptions which cannot be taken for granted. Even texts which most would not describe as political (such as a children’s book) have inherent biases of what it considers valuable, and one should always consider the causes and effects of these assumptions. For example, some of the novels about the “Old West” which Abel used might have been merely considered popular works in their time, completely disconnected from a political reality: they were just “fun” tales about “Cowboys and Indians.” However, given the retrospective of a hundred years, more people now understand their problematic depictions of indigenous peoples and the importance of challenging these politically motivated representations. Ultimately, there is no way to express oneself without being at least subconsciously political.

Print and Digital Art:

I wanted to develop a digital recreation of my poem, as I thought it would look more visually appealing, since the crooked strips of paper would be replaced by orthogonal text boxes. However, I quickly realized that moving text boxes around a word processor is actually a less precise method than moving around strips of paper. Add to that the fact that the document consists of nearly 16,000 words contained on one page, and you get a computer which started to lag considerably. Considering this, I am not entirely sure why I created a digital reproduction when I have a perfectly nice-looking physical version, but I think this speaks more generally to the relationship between digital and physical texts.

In particular, this lab involved a text originally printed in a book a hundred years ago being converted into a publicly-accessible digital document, which was then data-mined to create a private digital document, which was then printed out and physically modified to create a physical work of art, which was finally recreated using digital means. This constant conversion process between the digital and the physical shows how they are in conversation with each other, but that in each conversion, something has to be lost or omitted. When moving from physical to digital, one loses that tactile sense of paper which can be integral to one’s understanding of a text (just look at the pages in Abel’s “Injun” where the text appears upside-down). Additionally, in the conversion from digital to physical, one loses the wealth of meta-data and computational power stored in electronic files. (A Word file contains more data than a printed-out Word document, even if not all that data is readily accessible). While the physical and digital can imitate each other, they often inaccurately depict each other.

This could be one of the reasons for why Abel chose to physically publish his book: to demonstrate how information is lost in these conversion processes, leaving us with a misrepresentation of the original idea. Historically, indigenous voices have been filtered through a settler ideology, meaning many cultures have been improperly represented in literary culture, leading to grand misconceptions being developed about them. Abel demonstrates this loss of data in his poem and expresses the violence and inequity which result from this lack of communication.

However, there is also a positive relationship between the physical and the digital, as only through their connection could a project like Abel’s or mine be created. Through understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each medium, one can develop a meaningful perspective on how different methods of communication can be effectively utilized to create something meaningful. Through this relationship, new art can be formed.

To be more specific, I believe that anything can be art if one interprets it as such. Thus, due to how my poem depicts my relationship to the physical, the digital, and my Jewish identity, it presents itself as art to me. Moreover, I consider it to be valuable, as it provides insight into my personal perspective of the world, and I believe that any text which attempts that (which is basically every text) has some value. These notions are somewhat ambiguous, and I know many have written countless volumes attempting to define art and value, but I think attempting to create a universal and objective definition becomes a self-contradictory pursuit. Ultimately, the way I determine if something is art and if it is valuable is by asking, “Is this art to me? And is it valuable for me?”

Anything else would be assuming too much.