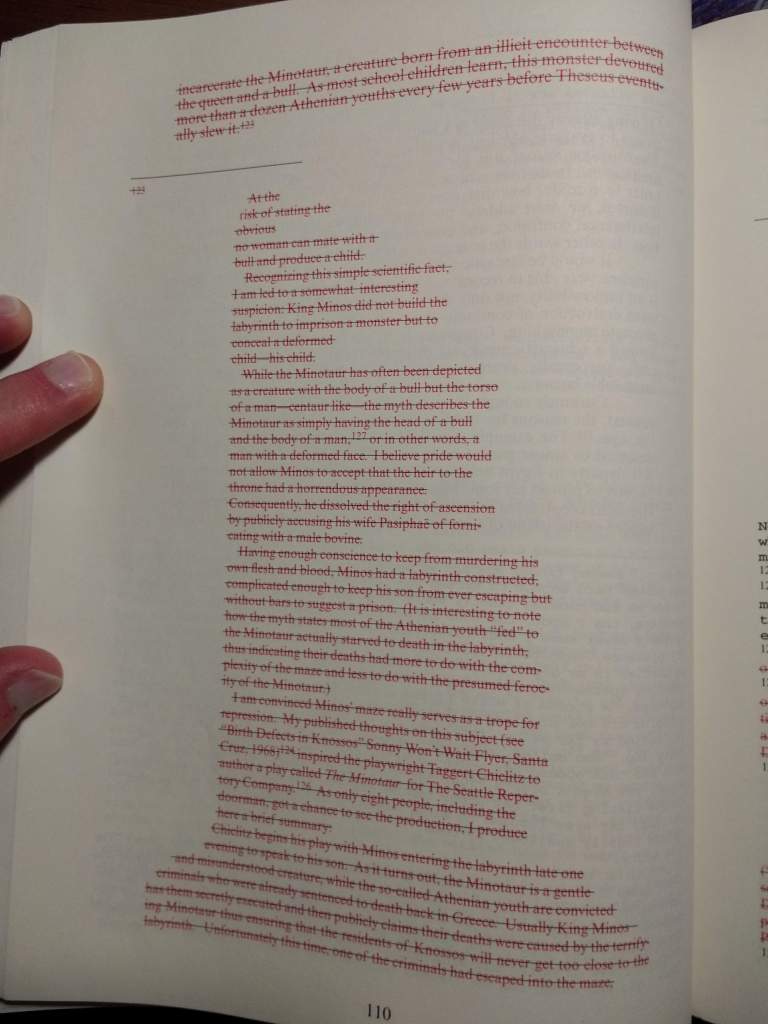

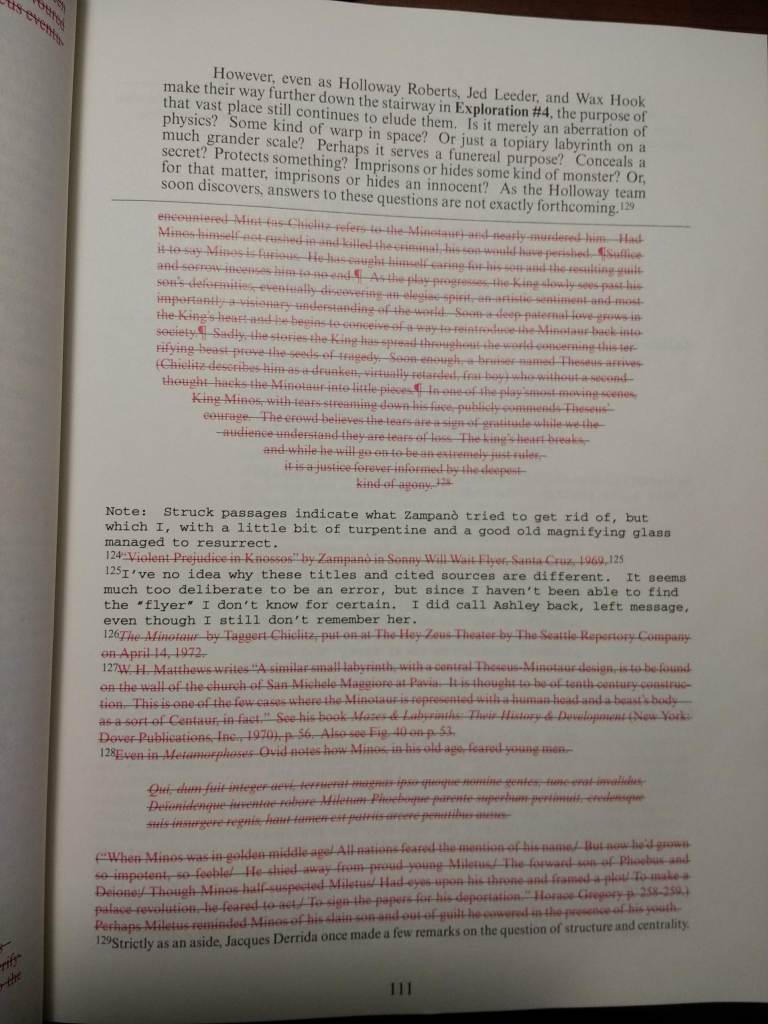

Mark Z. Danielewski has become well-known for experimenting with typography in order to provide additional visual meaning and intrigue to his texts. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Chapter IX of House of Leaves, where form, content, medium, and material all coalesce to depict a labyrinthine structure of text while describing the maze-like qualities of the house itself. Any page in this chapter could be taken as an example of experimental typography, but the ones which struck me the most (pun intended) are presented in the images below:

In particular, in developing its relationship between content and form, this passage complicates the relationship between Zampanò, Johnny Truant, and the reader and how it mirrors and challenges the mythological relationship between the ancient Greek figures of Minos, Daedalus, and Theseus.

The most obvious typographical element of this passage is its use of red-colored and struck-through font, which already demonstrates a notion of attempting to hide one’s creation. A note by Truant mentions that the “[s]truck passages indicate what Zampanò tried to get rid of, but which [Truant], with a little bit of turpentine and a good old magnifying glass managed to resurrect” (Danielewski 111). This quote relates Zampanò to the labyrinth owner Milos, in that both attempt to obscure their creations (the passage itself in the case of the former, and the Minotaur in the case of the latter) within a maze, while Truant, acting like labyrinth-maker Daedalus, allows the passage to live on, albeit within the realm of a maze-like structure. Moreover, his usage of the word “resurrect” seems significant, as it demonstrates Truant’s godlike role as the editor of the work. He has the ultimate say on how the text gets represented, even if it contradicts Zampanò’s apparent intentions, so that he, like Ovid’s depiction of Daedalus, “to unimagined arts / … set[s] his mind and alter[s] nature’s laws” (Ovid VIII.189-190).

Moreover, the supposed evil of the Minotaur and the good of the Minotaur-slayer Theseus is brought into question, by how Zampanò describes the two. Specifically, he mentions that “Minos’ maze really serves as a trope for repression” (Danielewski 110), which the text itself visually depicts by not only being struck-through, but by also lying within a footnote of a struck-through passage. Zampanò attempts to repress his own work, but we as the readers bring it to the forefront of our attention and do not allow it to lie in peace. We attempt to brave the labyrinth and look past the lines obscuring the text, but in doing so, we risk getting lost in the intricate details of maze of text, ignoring the larger picture. The passage mentions that “most of the Athenian youths ‘fed’ to the Minotaur actually starved to death in the labyrinth, thus indicating their deaths had more to do with the complexity of the maze and less to do with the presumed ferocity of the Minotaur” (Danielewski 110). Extending this metaphor of the readers being like the Athenians traversing the labyrinth, we can easily give up on the text in this chapter, leaving the integrity of the maze whole, accepting its complexity. Conversely, if we wish to plunder the labyrinth of words and slay the textual Minotaur, we would become like Theseus, whom Zampanò describes as a “drunken, virtually retarded, frat boy … who without a second though hacks the Minotaur to little pieces” (Danielewski 111). If we want to break free of Chapter IX, we will necessarily break through the loop of references and footnotes, ignoring the grand structure it attempts to set up. Moreover, by analyzing individual passages of the text, we cut it up into little pieces, and while these are more manageable, we ultimately forsake the form of the whole. The text seems to leave us with a lose-lose proposition: we either stop reading and perish in the maze, or we force our way through the text and obstinately destroy the sanctity of the work. One of the first things the novel tells is “This is not for you” (Danielewski ix), and by ignoring this message, we have become intruders in the realm of the novel, inserting ourselves into a place not designed for us.

Works Cited

Danielewski, Mark Z. House of Leaves. Pantheon Books, 2000.

Ovid. Metamorphoses. Edited by E. J. Kenney. Translated by A. D. Melville, Oxford University Press, 2008.