I thought about writing this blog post entirely with emojis, but I realized how difficult that would 🅱️, so I opted to use standard English (mostly). Many people underestimate the power of emojis to convey ideas, while others may use them too liberally, effectively obscuring meaning, so attempting to write an entire literary piece using only the images was quite a difficult challenge. Instead of creating a linear narrative, like Xu Bing’s Book from the Ground, however, I decided to 🅱️ a little more abstract with my work, with emojis not always representing what they initially portray and by using figurative “language.” I think it was successful, and I am extremely grateful for the two friends who were brave enough to write translations, as I am sure it was a difficult task.

Here is my emoji poem:

🧍♂️⛰🗣: “🗺🙏⚰🕳.” 😎 🍃🔊, 🐿🦅, 🔊👂,🌍🗣 “🙏😈❓ ⚖💲💀 🤜⛏💎 🕳😒 🥺,📏 🦶😇, 🤏,😢,💪 🏋️♀️🌏🤝❔” 🧍♀️⛰🗣: “⏳ 😔 🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂🙂 🤢🤢🤢🤢🤢🤢🤢🤢🤢🤢🤢🤢 🌎😱. ⌛😲💀💀 ⚰🌳🌷🌸🌹🌺🌼🌻💮🏵. ❤💙💚💛💜☠. 🌼💀👶, 😴🐍👭, 🔊🐶😏👨⚖️, 🤥✨, 🌱🧠 🌸😓🐍. “⏳,😇😈 ⏳🎗, 😨👎🔁 😫💲. 💳💸,🤑, 👉👉👉👉👈👈👈👈 😋🙃😵🥴🤬🤬🤬🤬 🚫☮.👇👇👇👇 😠😠😒😒😡😡💢💢 ⌛⌛.⌚; 🎁.👿 💀💀. 🕊🕊🌐,😀😁😃😄😊😍😘🥰☺🤗.” 🌍☮,😭, 😔.

Here is one of the two translations:

A boy went to the mountains and said: “I hope the map is right and we don’t fall into a pothole and die.” Sunglasses on Leaves crunching, Squirrels and birds, I heard, the world said “You pray to the devil? Try to find balance and not work to death Work hard for jewels Look into the dark hole and be sad Oh no, measure yourself You’ll set foot in heaven, Take things, cry, and be strong You’ll lift the world for friends?” A girl went to the mountains and said: “Time I am sad I am very very happy I am very very sick Oh look at the world. Time is running out and I will die And be buried in the pretty flowers. With lots of love in death. Flowers bloom and death turns into life, I sleep and there’s a snake and two women, I hear the dog of the businessman, I see snow, Thoughts grow There are flowers and I’m sad because of the snake. “Time, angel and devil Time takes lives, Oh no we must go again I need more money. I found money, happy, It’s not my fault it’s your fault I’m happy but it’s getting bad again No time for peace. I go down I’m angry and soon I will cease to exist Time runs out. Quickly; Present. Devil Death. Doves bring peace to the world, and people are happy and loving.” World peace, tears of joy, Sadness.

And here is the other translation:

A man climbed a mountain and then said “I hope to travel everywhere before I inevitably die and fade into black.” He was confident that he would. But then he listened to sound of the leaves in the wind The gnawing of the squirrels and the screech of the eagles, Just listened and listened, and nature said “Do you know of the evils of travel? The injustice and greed and death The violence and resource overuse The pits it creates hidden off to the side I beg of you, can you measure Your footsteps in a pure way, In small steps, in tears wiped away, in strength used To lift up the world and create agreements?” A woman climbed a mountain and said: “Time passes And it’s a sad truth that in life There is both sheer happiness in And overwhelming disgust at The shocking state of the world. One day it struck me that soon I would die. I pictured myself buried in a coffin covered with daisies and tulips and sunflowers and hibiscuses. And thought about how with my death so too would die my love for not just men but also women. Thoughts of flowers and death and life, They awoke within me a thirst for forbidden knowledge and so I pursued a woman I fancied, And eventually we welcomed a dog’s bark into our family as we pursued marriage before a judge, But society lied and the stars we had chased twinkled out of existence, And so grew in my mind The image of flowers on my coffin as a reminder that society forbids me the knowledge of free marriage. “Time passed, and neither angels nor devils favoured me for After an endless wait we learned that my lover had stage two breast cancer, With shock and frustration I felt as though my world had been spun on its head For at our darkest time we also struggled for money. Mounting credit card bills had flown all of our money away, yet we continued to spend, And then we fought and pointed fingers with accusations Of gluttony of frivolity of ignorance of confusion that grew increasingly hostile And it felt like we wouldn’t find peace. And so the downward spiral continued Of anger and mistrust until we both exploded And so time passed and passed. We watched the clocks; Until finally we got a gift. That evil cancer Had at long last died. We exchanged olive branches and reconnected, and in elation and celebration fell back in sweet love.” The world may never find peace, unfortunately, A disappointing truth.

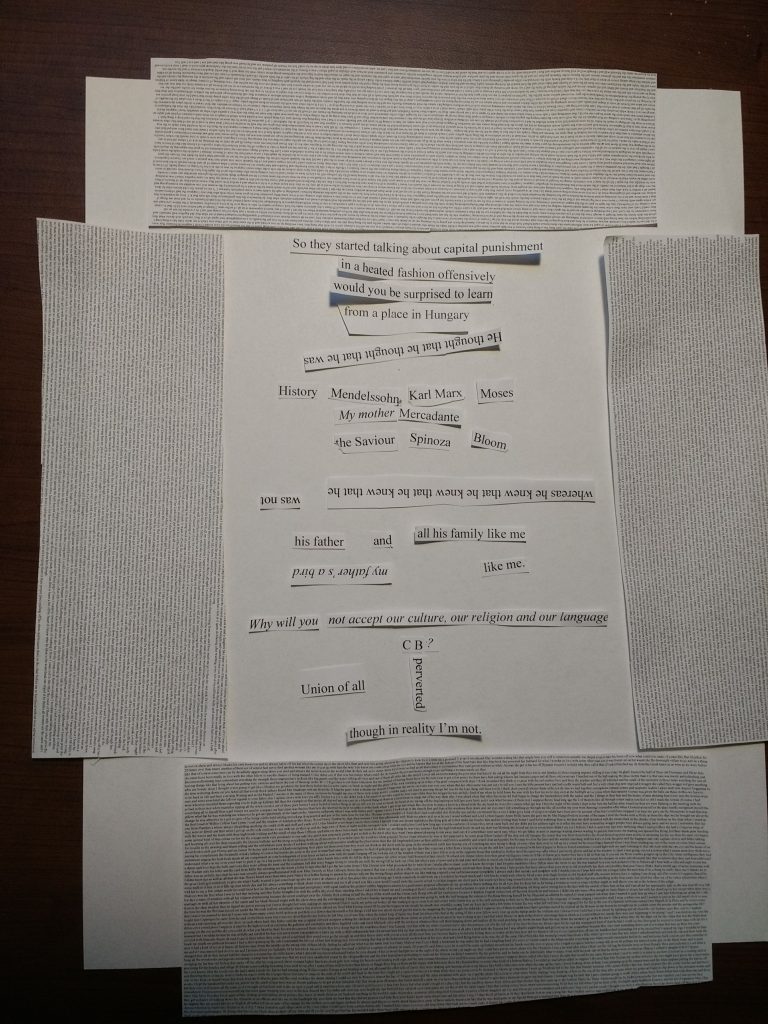

Composition

In composing my emoji poem, I first wrote down my ideas in English (which I am not reproducing here, because I do not want to influence the reader’s interpretation), and then I attempted to portray them as accurately as possible using the image-based language. I would type the main words and concepts into an emoji keyboard, hoping they would have equivalents, but more often then not, I had to resort to using emojis which represented similar, but not identical ideas. In some cases, I would use a sequence or collection of emojis, as in the line “⚰🌳🌷🌸🌹🌺🌼🌻💮🏵,” where I intended the emojis to not 🅱️ read individually but as a single, holistic image.

This process definitely contained more limitations than when reading and translating Bing’s novel, because I was forced to transform my ideas from a subtle, nuanced language into a less descriptive writing system, instead of the other way around. Frequently, I found that there was not a single emoji that would perfectly portray my thoughts, such as there being no emoji for a flower in the process of blooming. Additionally, the concept of time was a central theme for my poem, but the selection of emojis for depicting this idea is rather limited, so I was forced to reuse some of them, reducing the shades of meaning contained in the original text. It is difficult enough to describe complex thoughts and emotions in a nuanced language like English, so forcing myself to explain these in a language with an even more limited vocabulary was somewhat frustrating, at least initially. I eventually became more accustomed to using the emoji keyboard, and by the end, the process became a little more manageable, but surely never completely seamless.

Translation

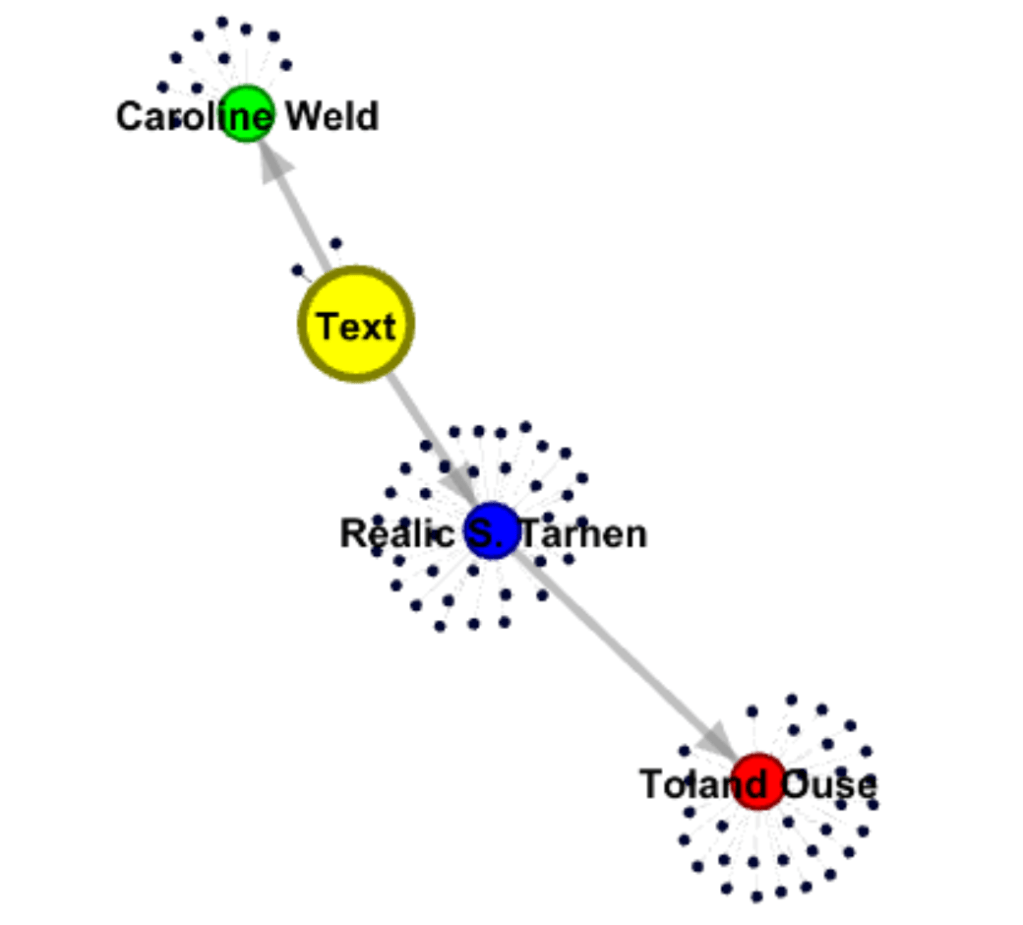

I decided to have two friends translate my poem, so that I could examine the different ways in which people could interpret emojis. I will readily admit that my text was difficult, maybe even too much so, but I am thrilled at what they both ended up writing. The first translator, whom I will refer to as K, was by far more literal in their interpretation, while the second translator, who will 🅱️ called D, interpolated more from the limited data presented, even though the latter translator still had a fairly literal interpretation. This reveals one of the potential misunderstandings that can arise when using emojis: some people wish to imply much more than others when using the images, leading to varying degrees of understanding. One sees the sequence “😴🐍👭” and thinks “I sleep and there’s a snake and two women” while the other interprets it as, “They awoke within me a thirst for forbidden knowledge and so I pursued a woman I fancied.” The second translator, D, by referencing “forbidden knowledge” may have been thinking of the Garden of Eden during this line (which is quite accurate, because I was thinking a bit about Paradise Lost when writing this poem), but both interpretations are completely valid, as such a text provides as much openness as a work of visual art.

Overall, both translations were relatively accurate to my original text, especially in picking up the themes of time, death, nature, and money, but they each had their own take on some of the more complex segments. For example, the second translator focused on ideas of gender and sexuality in the second and third verses, which was something I wanted to depict, but was not consciously thinking of all the time. It was interesting to see how this narrative arose throughout D’s translation, and I am glad that they were able to catch onto that thread and carry it through more fully than I originally planned.

Meanwhile, I enjoyed K’s more concise interpretation, because it attempted to replicate a potential effect of emojis by throwing out single word images in rapid succession. If we take the translator’s job to present a text in a different language, while attempting to keep it as close to the original as possible, K’s translation seems to do the job nicely. This type of translator has the difficult task of staying close to the original text while completely changing the language, so I respect what they accomplished with the poem.

All that being said, here are three core similarities and differences between the translations and my original poem:

Similarity #1: Themes of Time and Death

This similarity feels somewhat straightforward, as I used several emojis associated with ideas of these themes, meaning there should not 🅱️ any surprise that the translators would pick up on them. I think these ideas are so central to human society and culture, that they are fairly easy to notice in a work, even if the emojis for these concepts are fairly eurocentric (as represented by the coffin and the hourglass).

Difference #1: The Use of Flowers and Nature

I used various flower emojis throughout my poem to convey a sense of nature and its relation to life and death, but both translators interpreted these much more literally than I anticipated. Wherever I used flowers, I thought of them more as a sign for the natural world, and less as literal signifiers for a specific type of fauna, which alters some of the meaning in the poem. I wanted to place nature in conflict with humankind and society, but I do not think that idea came through fully in either of the translations.

Similarity #2: Finance and Jewels

Another important motif throughout the poem is ideas of finance and its relationship to human society. While both translators were somewhat more literal than I intended when using these images, they both recognized its importance and incorporated it nicely into their translations. K focused more on the constant desire for more wealth which society places upon us, while D examined that desire’s effect on the world’s environment and on the individual’s psychological state. Both perspectives are important to consider, and I enjoy how they each portrayed them.

Difference #2: Figurative Language

There were some instances where I attempted to use figurative language and “wordplay” in the poem, which did not quite appear in the translations. I understand that this system partially depends on looking at the world through the structures of the English language, however, which will inevitably create a dissonance in my intentions and another’s interpretation. For example, both translators interpreted the phrase “🌱🧠” as thoughts growing in the mind, while I intended the image to 🅱️ more akin to thoughts being implanted in one’s mind, which eventually grew into general ideologies causing distress, as indicated in the following line: “🌸😓🐍.” While the shade of meaning is slight, some of the forcefulness of language was lost in the translation process.

I am also somewhat disappointed that neither caught my wordplay, “⌚; / 🎁,” which was supposed to mean something akin to “the present is a gift.” It is a somewhat silly joke, but I was a little disheartened that neither of them noticed the pun.

Similarity #3: Sentence Structures

One thing both of the translations mirror perfectly is the use of punctuation and sentence structure (even if they have some comma splices and run-on sentences). This likely stems from the fact that punctuation is an inherent part of our (English) notions of language, so it is something to grab onto and mimic in such a translation exercise. Punctuation generally helps organize our written thoughts, so it is natural to follow this general structure.

Difference #3: The Ending

This may seem subtle, but I think it has an important impact on how one interprets the poem. Specifically, the last stanza in the original emoji poem states, “🌍☮,😭, / 😔,” which K translates as, “World peace, tears of joy, / Sadness,” and D as, “The world may never find peace, unfortunately, / A disappointing truth.” Both of these are more cynical than I intended, with K’s translation being a little bit closer to my intentions, while D’s maybe picks up on more of the subtext I went for. The crying emoji is ambiguous, as it can 🅱️ interpreted as joy or sorrow, and I was going more for the former. Moreover, I intended the emoji in the final line to depict a sense of relief, but also a feeling of hesitance toward hoping for peace on Earth, but both translators took this image as conveying sadness. As I have implied before, their interpretations are completely valid, and my intentions should not determine how they think about the poem, but I was a little disheartened at their general pessimism.

Digital Humanities

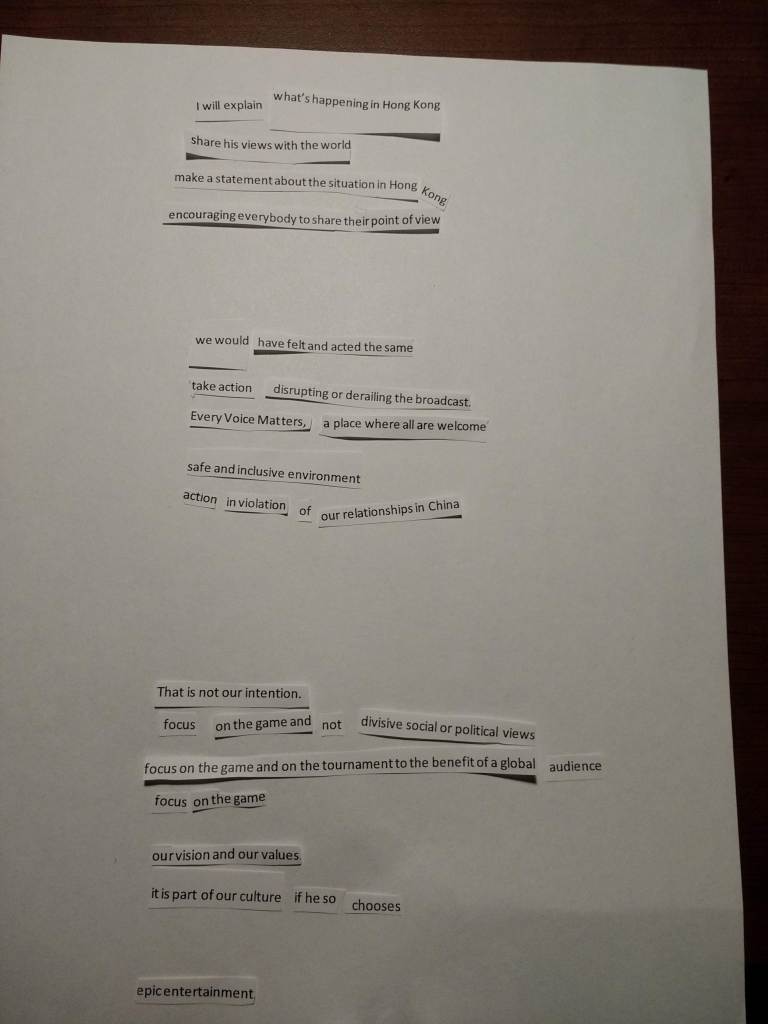

One thing this lab gave me an appreciation for is the potential digital technologies provide in presenting thoughts and ideas to a larger audience, regardless of language barriers. While emojis are still influenced by cultural norms and perceptions of society, they can convey concepts to a wider general audience, breaking through social barriers.

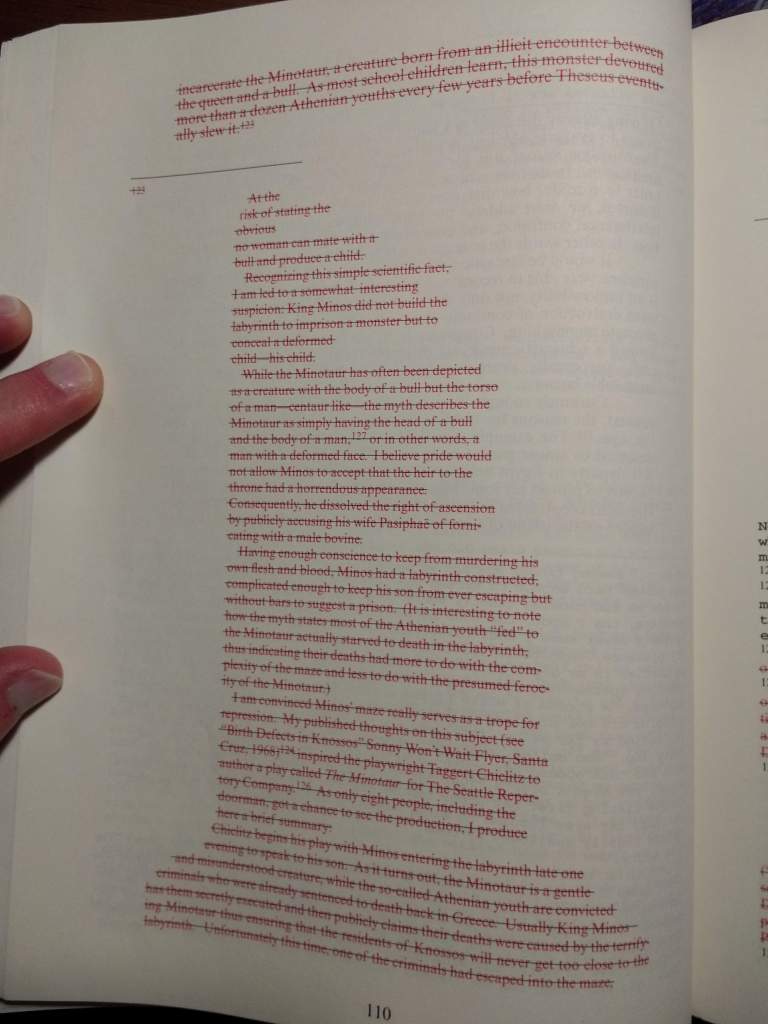

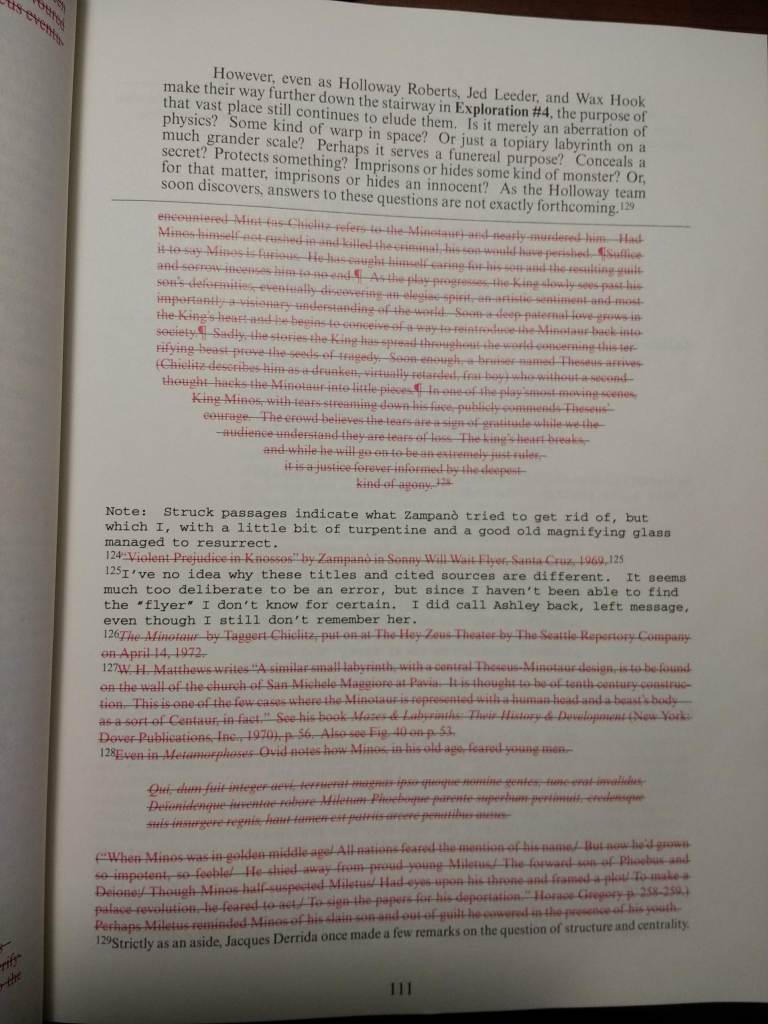

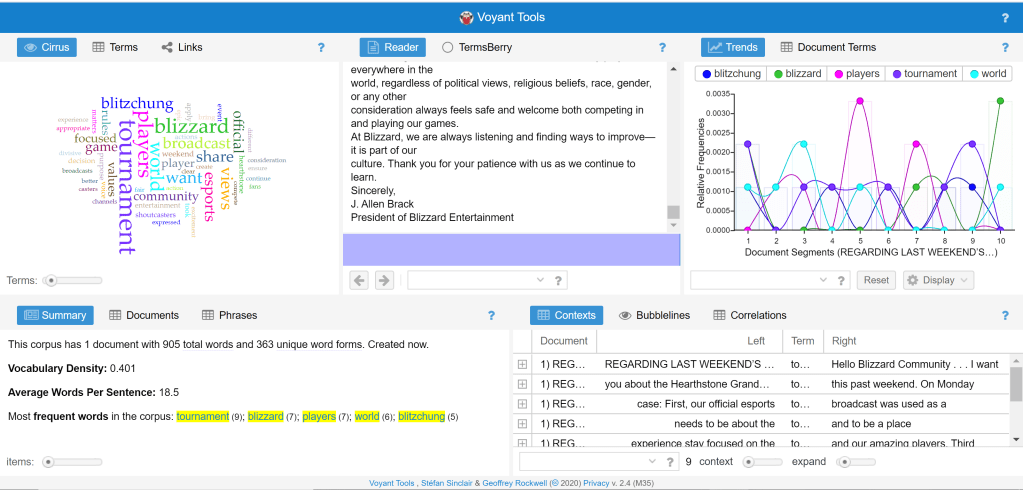

Moreover, this lab shows the variety in forms of ergodic literature, as it does take non-trivial effort to translate emojis into one’s language of thinking. I had previously considered this perspective on literary theory to focus mainly on interactive texts and intense, formally complicated works, like Danielewski’s House of Leaves, but I now realize that even linear and seemingly straightforward works of literature can 🅱️ examined under this lens. Any digital-born text which one cannot simply read as a traditional work can provide a glimpse into how we read and understand texts, demonstrating that our interpretive processes may not 🅱️ as simple as we may initially believe. Any text, whether written in emojis or some traditional language, must necessarily 🅱️ translated in the mind as it is read, because how one thinks of words and language varies from person to person. Sometimes one performs that translation process subconsciously and automatically, as with traditional literature, and sometimes one must consciously examine what the “words” represent, as with an emoji story. But in either case, there is a disconnect between the message that is sent and the one that is received.

Thus, as a digital-born text, an emoji poem demonstrates a fundamental philosophy of Digital Humanities, in attempting to bring the world (i.e. humanity) together through advances in technology, while simultaneously acknowledging a latent futility in truly grasping the subjectivity of another. We are all like robots, connected to each other through a network of ideas and possibilities, but our connections will always 🅱️ limited by inefficient hardware and unforeseen, and sometimes catastrophic, glitches.